Prologue

On September 11, 1959, Frank Serpico joined the New York City Police Department as a probationary patrol man.

On 3 February 1971, he pretended to make a drug purchase and attempted to make drug dealers to open the door. A suspect opened the door a few inches. He wedged his body in. He asked his colleagues to help. They ignored him. The suspect shot him in the face with a .22 LR pistol. The bullet struck just below his eye, lodging at the top of his jaw. He began to bleed profusely. He fired back striking his assailant to the floor.

Ten-codes represented common phrases in voice communication. This reduced use of speech on the police radio. The other party asked over the radio, “Do you read me?” A reply “10-2” meant “receiving well.”

In those days in the New York City Police Department, a shout of “10-13” on the radio indicated that an officer had been shot and assistance was required.

His colleagues refused to make a “10-13” dispatch to police headquarters. An neighbouring elderly man called emergency service and stayed with him. A police car arrived. They learnt that Serpico was a fellow officer. They took him in the patrol car to hospital.

The shooting happened 8 months before he and David Durk were about to testify before the Knapp Commission. Serpico was the first police officer in the history of the New York City Police Department to step forward to report, and subsequently testify openly about widespread, systemic corruption pay-offs amounting to millions of dollars.

Serpico and Durk became allies since 1967. They teamed up to breach the aptly named ‘blue wall of silence’. They complained to high-ranking police and City Hall officials against police corruption. They gave names, dates, places and other information, but were told that nothing could be done.

The Knapp Commission

According to New York Times, Excerpts From the Testimony by Serpico, 15 December 1971, Serpico said:

Through my appearance here today … I hope that police officers in the future will not experience … the same frustration and anxiety that I was subjected to … for the past five years at the hands of my superiors … because of my attempt to report corruption. I was made to feel that I had burdened them with an unwanted task. The problem is that the atmosphere does not yet exist, in which an honest police officer can act … without fear of ridicule or reprisal from fellow officers. Police corruption cannot exist unless it is at least tolerated … at higher levels in the department. Therefore, the most important result that can come from these hearings … is a conviction by police officers that the department will change. In order to ensure this … an independent, permanent investigative body … dealing with police corruption, like this commission, is essential …

A video introducing Frank Serpico is available here.

David Durk’s moving testimony before the Knapp Commission is available here. He told the commission:

Corruption is not about money at all, because there is no amount of money that you can pay a cop to risk his life 365 days a year. Being a cop is a vocation or it is nothing at all, and that’s what I saw destroyed by the corruption of the New York City Police Department, destroyed for me and for thousands of others like me.

In 1975, Durk took a year’s leave at the United Nations to study crime issues. In 1979, he took another leave to work in the city’s Finance Department. In 1985, he retired on a police pension of $17,000 a year. He died at 77 in 2012.

On 15 June 1972, Serpico retired. He stayed in Switzerland and the Netherlands for almost a decade. He also travelled in Europe during 1979 to 1980. In 1980, he returned to live in a secluded cabin in the woods north of New York City.

Dirty Harry Problem

The “noble-cause corruption” is often summarised as the “Dirty Harry” problem. Does “good ends” justify “dirty means”?

The name came from the 1971 American film played by Clint Eastwood as San Francisco Police Department Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan. An introduction to the film is available here. The original theatrical trailer is available here.

The “Dirty Harry” problem is important for 3 reasons:

It is perverting the course of justice by police officers.

Perversion by police is the more frequent complaints from members of the public about police misconduct.

Police culture and performance targets increase the pressure on police officers.

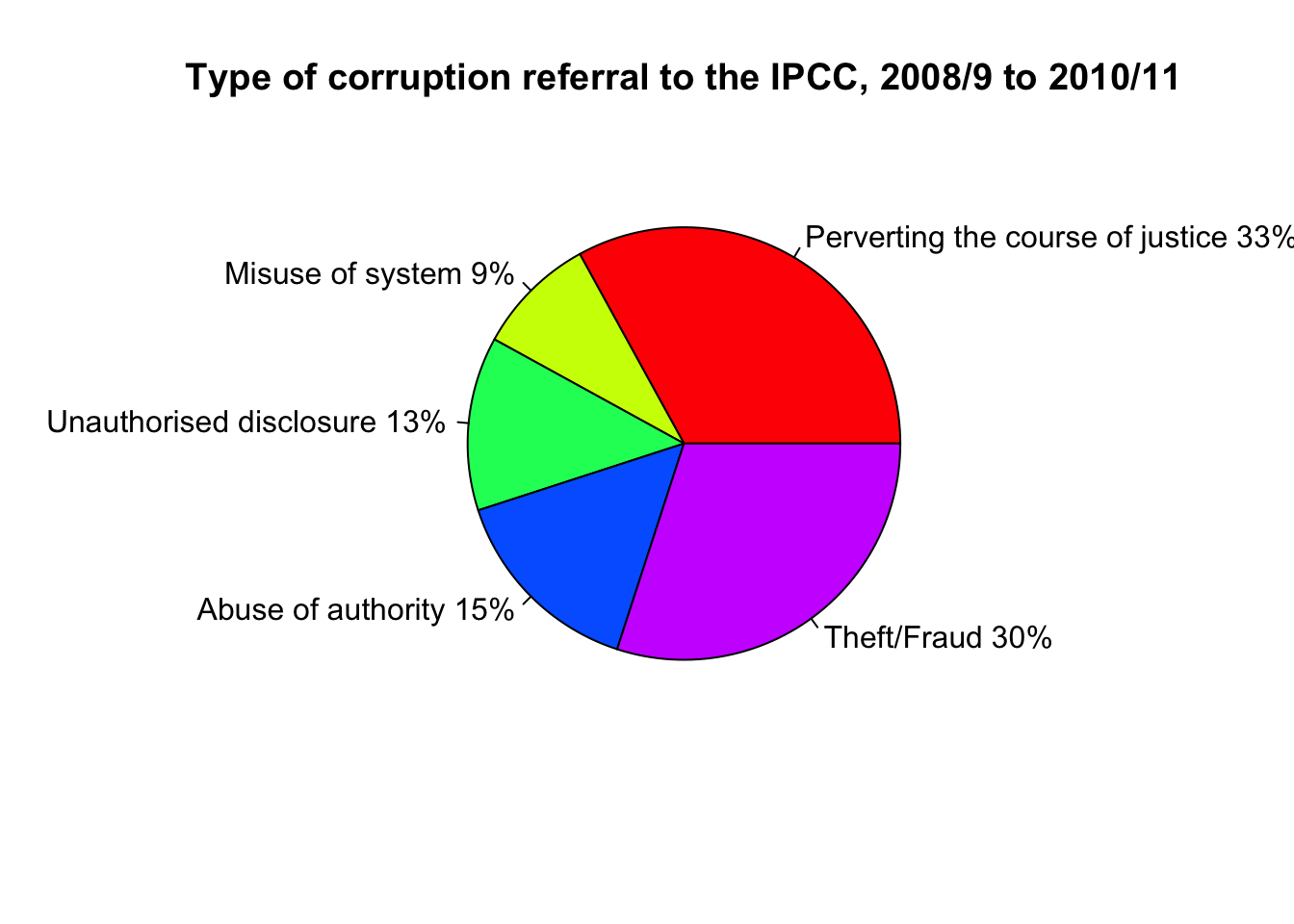

The following figure explains the distribution for 5 types of misconduct referral to the Independent Police Complaints Commission of England and Wales from 2008/9 to 2010/11. It was reproduced from the literature review of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The 5 types of misconduct (corruption) are:

Perverting the course of justice: includes falsification of records or witness statements, perjury, and tampering with evidence

Misuse of systems: includes the unauthorised access of police systems for personal gain, including on behalf of friends or family

Unauthorised disclosure: includes the disclosure of personal details of offenders, suspects or civilians; crime report information; or information that could jeopardise a court case

Abuse of authority: includes the abuse of the trust or rights of a colleague or civilian and the misuse of police power and authority for organisational or personal gain

Theft/fraud: includes theft while on duty; fraudulent expense or overtime claims; and unauthorised personal use of police credit cards.

Epilogue

Police work in a complex moral world. They must recognise that they are asked to make difficult ethical decisions daily.

He who does battle with monsters needs to watch out, lest he in the process become a monster himself. And if you stare too long into the abyss, the abyss will stare right back at you.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse, Nr. 146 (1886) in: Werke in drei Bänden, vol. 2, p. 636 (K. Schlechta ed. 1973) (S.H. transl.)